Knock Three Times: Girlhood, Ghost Stories, and the Movie That Found Me

Tony Orlando & Dawn: Knock Three Times

Film and Soundtrack: Now And Then

Audio Book Style

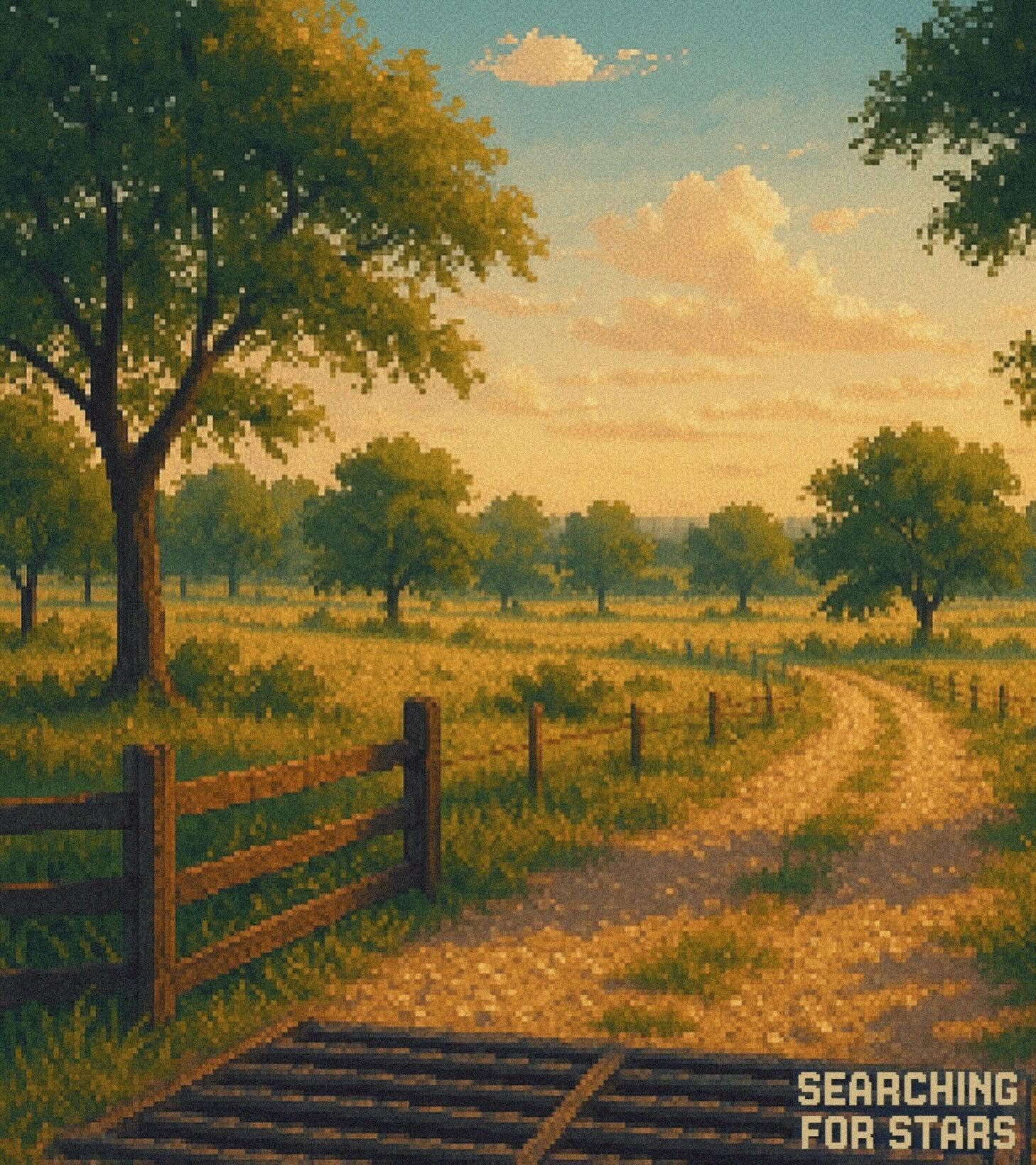

I don’t remember what season it was—only that the living room was warm and I was wearing my favorite outfit: denim overalls, blue tights, and my Nike sneakers that made me feel fast and important.

The wood-burning stove hummed in the background like an old song. My parents were probably at the kitchen table playing cards or talking conspiracy theories with Jimmy and Marie. It was the kind of house that felt like magic and safety in the trees.

We called it a farm, even if it wasn’t one. There were animals—rabbits, a donkey—and there were woods and games and peace. It felt like a retreat. It felt like a place where real life couldn’t reach us.

April, their daughter, had the movie. I don’t know if she bought it, borrowed it, or recorded it off something, but she was the one who pressed play. She was older than me, cool and sweet and effortlessly kind, and she never made me feel like the little kid tagging along.

I sat on the couch that day and watched Now and Then for the first time, and it imprinted itself on my soul.

The music. The mystery. The movement between then and now.

It was the best movie I had ever seen. And I remember knowing, even before the credits rolled: this one was going to live in me forever.

I was probably around nine years old—somewhere between still-believing-in-magic and just-starting-to-ache.

And Now and Then felt like both.

The way it moved between childhood and adulthood, between bikes and babies, seances and sorrow—it was like someone had written it from the inside of my own little soul.

Samantha was the character who grabbed me.

She was the quiet, steady one. The watcher. The writer. She felt the most like me—bookish, thoughtful, carrying more than she said. Her parents were separated, too, and the movie didn’t shy away from that ache. It didn’t make it dramatic or clean. It just… was.

Watching her felt like finding a mirror.

I didn’t have the words for it back then, but something in me clicked. I knew I wanted to be a writer. That’s what I saw when I looked at Sam—not just a character, but a glimpse of my future self.

That was the magic of the movie. It didn’t just entertain me. It told me something. About who I was. About what I could become.

Even now, I remember sitting there—legs curled up under me, heart open like a notebook—and thinking, This is the kind of story I want to live.

Long before I saw Now and Then, I knew “Knock Three Times.”

My mom sang it all the time. Sometimes in the car, sometimes just out of nowhere—like the words were always waiting at the edge of her lips, ready to lift the air around her.

It was one of the first songs I remember hearing her sing. Part of a mixtape her friend John made her—this homemade time capsule of Billy Joel, The Beatles, and Tony Orlando and Dawn. That tape floated around our lives for years until eventually, it was mine.

“Knock three times on the ceiling if you want me…”

I can still hear her voice in my head when that line plays. Not just singing it, but loving it. Smiling with it.

So by the time that scene lands in Now and Then—the girls singing it at the top of their lungs, riding bikes through the streets of their childhood—it wasn’t just fun.

It was familiar.

It felt like watching my mom’s voice come to life on screen. Like memory had cracked open and spilled across the movie.

And suddenly this film wasn’t just a story. It was a place I’d been. A song I knew. A feeling I recognized.

And the strangest thing happened: even though I was a little girl watching other little girls on screen, it somehow felt like I was also watching my mom’s childhood.

Like this fictional 1970s world the girls were riding through was the one she had grown up in, too.

That moment, that song, that scene—it stitched something together in me. Girlhood and motherhood. Past and present.

A bridge across time, held together by music and memory and the sound of a voice I’ve always known.

Not long after I saw the movie, a group of girls at school started pretend-playing Now and Then.

They were assigning characters, calling dibs, building their own little version of the story at recess. And when it came to me, one of them said it flat out, like she was handing me a flaw:

“You can be Samantha… since your parents are divorced.”

I remember the sting trying to rise in my chest—but it didn’t land.

Because the thing was… I wanted to be Samantha.

She was the one I had already chosen in my heart.

They thought they were boxing me in. But what they didn’t know was that I had already seen myself in her. I had already felt that connection light up like a string of stars between me and the screen.

I liked her quiet. I liked her depth. I liked that she was a writer, a thinker, a little set apart but always paying attention.

So I didn’t flinch.

I just shrugged—maybe a little smug—and thought, Fine. I wanted to be her anyway.

I’ve watched Now and Then more times than I can count.

As a kid, I wore it out—rewinding the VHS, mouthing the lines, feeling like the fifth member of the crew. Back then, the adult scenes felt like background noise. Something to sit through before we got back to the bikes and the seances and the lake.

But the older I got, the more those grown-up scenes started to matter.

They weren’t background anymore. They were familiar.

Watching it now—as a mom, as a woman, as someone who’s carried her share of grief and grace—it’s not just nostalgia. It’s a mirror.

I still see myself in Samantha. Maybe even more now. But I also see the others in new ways—Roberta’s anger, Chrissy’s innocence, Teeny’s bravado. I understand the weight they carried into adulthood.

And when I watch them gather again after years apart—older, changed, but still tethered to each other—I feel it differently.

That’s the gift of this film. It grows with you.

It’s a time capsule, sure—but it’s also a living memory. A story you can step into at any age and find something true.

The music from Now and Then didn’t just live in the movie—it lived in my memories of the Williams’ place, too.

That house out in the country—the one we called a farm—where animals roamed and laughter floated through open windows.

Where card games lasted for hours and Uno was sacred.

Where I learned to shoot a gun for the first time.

Where my dad and Jimmy Williams would sit for what felt like forever, talking about the Bible, the government, aliens, God—whatever strange thread of conspiracy or mystery they were chasing that day.

The whole place had a rhythm. A low hum of comfort and curiosity and something just left of normal.

And floating inside all that were songs like “Hitchin’ a Ride”, “All Right Now”, “I Want You Back” and even more greats.

Whether they were actually playing on a stereo or just etched into the feeling of it all, I don’t even know anymore. Some music just sticks.

The soundtrack became the sound of that era in my head—a mixtape for a chapter of life that still smells like wood smoke and feels like blue tights and denim overalls.

I couldn’t have told you what the 70s felt like.

But somehow, through that movie, that music, and that house… I almost could.

There’s one scene that always stayed with me so vividly.

Sam in the storm drain—screaming, crying, stuck in the dark—and Teeny reaching down for her, refusing to let her go.

Even as a kid, I knew everything would be okay. We’d already seen their grown-up versions. But it didn’t matter. I still held my breath every time.

Because that moment felt bigger than danger.

It felt like friendship. Like girlhood. Like the fear of being left behind and the deeper, braver part of someone saying: not you. Not this time.

That scene, that rescue—it meant something. Maybe because, in my own way, I was standing at the edge of something too.

The start of a storm I didn’t see coming.

My parents’ marriage unraveling. Life shifting. That season of almost-middle-school where everything feels like a question.

And I think I held onto that moment not just because it was dramatic, but because somewhere inside me, I needed to believe that someone would come back for me. That I wouldn’t be left behind in the dark.

The moment that changed everything wasn’t just when Sam got stuck.

It was who pulled her out.

For most of the movie, the old man was a ghost in their story. A shadow behind curtains. A whisper of fear that followed them from yard to cemetery. They thought he was dangerous. A murderer. A man with something to hide.

But when it mattered most—when Sam was screaming and stuck and no one else could reach her—he was the one who stepped in.

No hesitation. Just presence.

And in that moment, everything flipped.

Samantha finds out the truth: it wasn’t that he killed his family. It was that he lost them. That he’d been swallowed by grief. That the world had moved on without him, and he’d become a myth—because people didn’t know what to do with a sadness that big.

And suddenly, the whole story changed.

The ghost became a father. The shadow became someone with a name.

That moment still breaks something open in me.

Because it taught me that the things we fear the most aren’t always dangerous—they’re often just misunderstood. And that sometimes, the person we’ve been warned about is the very one who shows up when we need saving.

The lake scene in Now and Then gets me nostalgic every time—not because of the plot, but because of the feeling.

That soft, golden kind of freedom.

The kind that only exists in a certain stretch of childhood… when the heat doesn’t bother you, when your hair’s still wet from swimming hours ago, and you’ve got nowhere to be except wherever your bike takes you next.I was that girl.

The barefoot one. The tomboy. The one tearing through town on two wheels with blue tights, wild waves, and scraped knees.

I didn’t need a lake to feel like swimming—any ditch or puddle would do. Any muddy creek, any hidden runoff or overgrown drainage pipe. I saw water, and I was in it.

I actually got mono once from swimming in a dirty creek. I was maybe eleven or twelve. The doctor looked at me like, “You been kissing on boys?”

I was mortified. I’d never even been kissed!

Turns out you can get mono from swimming in dirty water too. Not everything wild and wonderful is without its consequences I suppose.

My crew was mostly boys—Joseph, Nathan, Waymon, Danny—and one girl, Carrie. We were little backroad adventurers. We rode for hours, raced to nowhere, told each other ghost stories and dared each other to jump into things we probably shouldn’t have.

We didn’t have treehouses like the girls in the movie were saving up for.

But we had each other.

And we had the open road.

I never did a seance, but I spent a lot of quiet time at Hopewell Cemetery. I used to walk between the graves, sit under the old trees and just… think. The dead didn’t scare me. They made me feel calm. Centered. Like the world had more to it than what I could see.

And that treehouse—God, I wanted one.

In the movie, it’s the symbol of everything: freedom, friendship, a place of your own.

I didn’t get one back then. But years later, my husband Jamie bought one—for our children, and maybe also for the girl I used to be. The one who watched Now and Then and dreamed of being high in the trees with a notebook and a view.

The dream took the long way around.

But it still found me.

If I could sit beside that little girl now—on the couch in the blue tights and overalls, the one who had just watched her first storm drain rescue and felt her heart change shape—I’d say:

You’re not wrong to feel this much.

You’re not wrong to believe stories can save you.

One day, you’ll write your own.

And it won’t all be easy.

You’re going to walk through things you can’t imagine yet. Some of it will break your heart. Some of it will build you. But through all of it, you’ll keep writing.

There will be music.

There will be stories.

There will be love.

And you, Princess Smilin Face…

You’ll carry your light, even when the sky goes dark.

Searching For Stars